The Startled Space: Susanne Langer, Rainer Maria Rilke, and the Resistance to Modernity’s Flattening

Reclaiming the Multi-Dimensional Temporality of Human Experience through Music and Poetry

Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the angels’ hierarchies?

[…]

In the end, those who were carried off early no longer need us: they are weaned from earth’s sorrows and joys, as gently as children outgrow the soft breasts of their mothers. But we, who do need such great mysteries, we for whom grief is so often the source of our spirit’s growth — : could we exist without them?

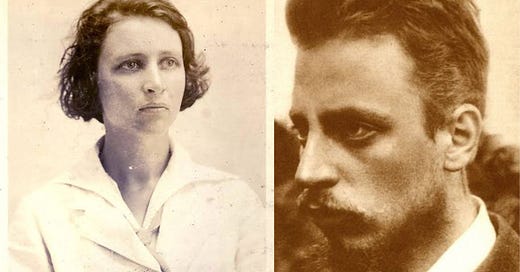

Is the legend meaningless that tells how, in the lament for Linus, the daring first notes of song pierced through the barren numbness; and then in the startled space which a youth as lovely as a god had suddenly left forever, the Void felt for the first time that harmony which now enraptures and comforts and helps us. — Rainer Maria Rilke; The First ElegyRainer Maria Rilke’s first Duino Elegy, quoted above, reflects several aspects of modernity and the Flattening¹ I wish to illuminate in the course of this essay. The context in which this poem came to be is just as important as the messages contained within. This article is about music, time, and Susanne Langer, but it is also about the role music plays in the modern condition, especially in this age of AI — a period I call The Great Flattening. But what exactly is ‘time,’ and what is being flattened?

The context in which this poem was born was a world before the Great War, at the height of Enlightenment ideals. The early 20th century was the realization of this ideal, which had been unleashed in the early stages of the Renaissance and accelerated through the exchange of ideas in the “Republic of Letters” during the time of philosophers like Descartes, Spinoza, and Leibniz. Central to this worldview was the belief that the universe is a knowable entity and that our role in its unveiling is one of rational discernment and categorization — Explication. We are not merely active Things among Things; rather, we see ourselves as detached observers, the architects of a palace of pure epistemological clarity. In this palace, myths of metaphysical ineffability and cosmic mystery are deemed by the code of this epistemological grammar as ‘not the case,’ rather our world is fully knowable within the logic of our discursive practices — a view that Rilke and Langer challenged vigorously.

Rilke’s Existential Crisis and the Great Flattening

This fully knowable, rationalized, and increasingly instrumentalized word found a young Rilke alienated and increasingly detached. He stopped writing and fell into what us Moderns call a writing funk. Unable to tap into his muse, Rilke experienced what German sociologist Hartmut Rosa deems a catastrophic silencing between himself and the world. Rilke’s resonant wire had gone mute. We also learn through ‘The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge,’ that Rilke was horrified by the fragmentation and chaos of modern urban life — the dissembling of that which is whole into incoherent parts for sterilization within the great Flattening regime of the early 20th Century. Seeking solace from this malaise, Rilke accepted an invitation from Princess Marie von Thurn und Taxis to stay at Duino Castle in Italy, where he hoped to find renewal in the wind, water, clean air, and expansive time of the seaside.

‘Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the angels’ hierarchies?’ — We know that the answer is no one thanks to Nietzsche’s. And this is what is so terrifying. The opening line of this poem was born on a day while Rilke walking along the shore; the wind was strong, and his mind had was occupied with a distressing business letter he had received that day. In that moment, as his historical being walked among the landscape, embodied in the raw elements of nature, his resonant wire activated, and the first of ten elegies would be born — a forceful re-inflating of the ontological Flattening Modernity had been inflicting upon all of us.

Thauma, Wonder, and the Terror of Modernity

In English there is no single word to capture the feeling of awe — that profound sense of wonder, and at the same time of being terrified. Kubrick’s ‘My god it’s full of stars,’ may be the most apt phrase we can relate this feeling to. But in Greek they had a word for this, Thauma (θαῦμα). Aristotle said that Thauma is the beginning of philosophy, the origin of our desire to understand the world around us. But also wrapped up in Thauma is a terror — ‘if I cried out, would hear me among the angels’ hierarchies?’

It is this terror, more so than the wonder and awe wrapped up in Thauma, that propels the modern condition with the relentless insistence which is embedded within the code of the epistemological grammar machine explicated in those Republic of Letters, the necessity to Explicate and Immunize —

What was background and saturated latency has now, with thematic emphasis, been transferred to the side of the envisioned, the concrete, the worked-out and the producible. With terror, iconoclasm and science, three latency-breaking powers moved into position whose effects cause the data and interpretations of the old “lifeworlds” to collapse. — Peter Sloterdijk Foams: Spheres III

The Second Battle of Ypres and the Death of the Old World

Decades after Rilke’s transformative experience at Duino Castle a through line can be traced from from the Republic of Letters, through the existential rift Rilke plumbed that day on the shore, right through to the hands gripping the shovels digging the trenches to fight a war a few hundred miles from the shoreline of Duino Castle.

The Second Battle of Ypres, infamous for the first wide scale use of ‘poison gas’ also bears witness to the haunting and incongruent — to us Moderns — presence of a Canadian Bagpipe regiment in those very tranches. Yet to these men, it was not incongruent, as this bagpipe regiment, their role within a code embedded in the logics of an order thousands of year old, was still legible, to many. The absurdity, the inhuman level of violence that are embedded within the mechanized tanks, and the scarred landscape, had yet to render the melodies, the spaces of wonder and awe silent — yet.

However, the old world officially died there that day, as the code inscribed in the Republic of Letters finally wrested control through the molecules of a ‘heavier-than-air’ chlorine gas. These disassembled, reassembled, indifferent molecules were strategically released into innocent air, until that moment, had always been a constant in the great chain of legends from time immemorial. Air, something never needing explication nor immunization from, was now something to be feared, to be questioned. The air, now rationalized and instrumentalized, abstracted from the very grounding of its cosmology by anonymous men enacting their prescribed routines in this new serialized regime of necessity, established once and for all the primacy of an ontology of distance, control, and fear.

The bagpipers, choking through their distorted melodies, were silenced as they collapsed into the fields, and the fields of resonance and order they were courageously fighting to reflate and reinforce were violently flattened. In its place arose a new plane of pure, detached, rationalized necessity. The Flattening won the battle of the old order that day — a day Rilke glimpsed while standing upon those shores. That existential chasm which opened before him as he pondered the sea, enveloped by an old wind, as his traumatized being sighed at the rapidly approaching wave of modernity — a force set in motion a mere 300 years before. There he stood, in dialogue with World, Self, and Time; he must write and build a space, a durable, flexible, pliable space, if just large enough to give the rest of us enough time for a few breaths; a chance.

The work of Susanne Langer picks up where Rilke left off, continuing the project he began that fateful day on the shores of Duino Castle. Langer’s work, particularly her exploration of music’s singular ability to express the full convolution of human experience, illustrates a method — a practice really — for us to slip our raw fingers between the seams of the space Rilke fought to reinforce, giving us a chance for a few more breaths to confront the Great Flattening that washed over Rilke and the World at the turn of the 20th century.

Susanne Langer’s Philosophy of Music and Virtual Time

Central to Langer’s philosophy is the idea that music possesses a unique ability to capture and convey the multiple dimensions of time each of us experience at any given moment. She calls this time “virtual time;” the complex, interwoven temporalities that shape our inner lives and mediate our relationship with the world. Her works, ‘Philosophy in a New Key’ and ‘Feeling and Form,’ explore how aesthetics, metaphysics, and symbols provide significant forms²— objective rational observations which enlarge our understanding of the world and can resists the Flattening.

Langer positions musical time in stark contrast to the scientific time that dominates modern life — the time of Einstein and the relentless tick-tick-ticking of the clock. For Langer, time is multidimensional and multifaceted, an ecology of overlapping temporalities, each with its own tensions — inter and intra — and resolutions.

‘The primary illusion of music is the sonorous image of passage, abstracted from actuality to become free and plastic and entirely perceptible.’

‘Music makes time audible, and its form and continuity sensible,’ Langer asserts, thereby objectifying and giving significant form to the continuous flow and qualitative richness of lived experience. It is in this capacity that music becomes a powerful tool for resisting the ontological violence of modernity, which seeks to reduce the depth and complexity of human temporality to a Flat, homogeneous succession of discrete, measurable moments.

This is precisely the challenge that Rilke confronts in his Duino Elegies, as he grapples with the existential weight of a world that threatens to sever us from the fullness of our temporal being. Like Langer, Rilke recognizes the vital role that music can play in preserving and affirming the multi-dimensional nature of human experience in the face of modernity’s flattening effects.

Rilke’s Invocation of the Lament for Linus

Rilke ends his first Duino Elegy:

Is the legend meaningless that tells how, in the lament for Linus, the daring first notes of song pierced through the barren numbness; and then in the startled space which a youth as lovely as a god had suddenly left forever, the Void felt for the first time that harmony which now enraptures and comforts and helps us.

‘The lament for Linus’ is the ancient Greek myth of Linus, a divine youth and musician, potentially the son of Apollo or Amphimarus, a muse. A prodigy whose life was cut short, tragically, by either accident or divine jealousy — this is unclear, but what is clear is that in the myth, the untimely death of Linus was mourned, profoundly, by God’s and mortals alike. The lament became associated with songs, that embodied the emotional torment of grief, despair, and tragedy. The tragic finds its significant form in melody and harmony, the multi-modal tensions and resolutions which give significant form to our complex relationship with World, ourselves, and time.

the daring first notes of song pierced through the barren numbness; and then in the startled space

The startled space becomes a site of resistance against the Great Flattening, a bulwark against the disenchantment and instrumentalization of the Modern world. Within the rattling, startled spaces that melody and harmony disturb, an opportunity emerges for us to push back against the totalizing silence pressing down upon us. That old wind finds form and power again, regaining its youthful vigor, and we now see the crucial project of resistance both Langer and Rilke provide — the tools, the methods, the courage, to resist, to push back and up against the stranglehold of a profane scientific time and reclaim this virtual time embedded within musical forms which articulates the depth, sensuousness, and irreducible significance of our lived experiences.

Yet it is the model for the virtual time created in music. There we have its image, completely articulated and pure; every kind of tension transformed into musical tension, every qualitative content into musical quality, every extraneous factor replaced by musical elements. — Langer ‘Feeling and Form’

Clock-Time vs. Music: Affirming the Ineffable Complexity of Being

Clock-time, like language, seeks to fix, to bracket, to abstract away from the multi-dimensional modes of temporal weaving, and the relational aspects of things — things which observe us, as Merleau-Ponty remarked — yet, this clock-time, scientifically bracketed-time, this onto-epistemological imperative to label, name, to declare and affirm that something ‘is the case;’ this obscene violence, meets a formidable opponent in music. Music, is an epistemological statement that affirms the quality of your temporal, affectual, and singularly unique being in world. You are not a datum, you are not a person, a laborer, a painter, a mechanic, a mother, a hero, you are in contradistinction to the Great Flattening code, an ineffable singular becoming being which music affirms to be the case.

This epistemological enlarging which enables the unveiling of previously hidden, and outright denied aspects of our reality, now demand further investigation, as Langer beautiful states: ‘which we can philosophize’ about. Such a statement is highly antagonistic to our current Western epistemological and ontological constructions. In modernity, something such as a musical expression, formulated in Langer’s sense as a significant form or a multitude of forms, cannot exists as an epistemological event. It is simply the case that in Modernity, only discursive means of uncovering knowledge are considered valid. This is at the root of our age of anxiety and our antagonistic relationship to the world.

I am so afraid of people’s words.

They describe so distinctly everything:

And this they call dog and that they call house,

here the start and there the end.

I worry about their mockery with words,

they know everything, what will be, what was;

no mountain is still miraculous;

and their house and yard lead right up to God.

I want to warn and object: Let them be!

I love to hear the singing of things.

But you always touch: and they hush and stand still.

That’s how you kill.

-Rilke ‘Poverty of Words;’ cited from Hartmut Rosa’s ‘Resonance’ pg. 229¹ The Flattening; The Great Flattening; We Will Not Be Flattened —This project aims to create a vocabulary, framework, and space that allows for the expression and significant form of our real, lived experiences in this age of AI and diminishing resonance. In this essay, The Flattening refers to the period before the rise of algorithms and AI, while The Great Flattening denotes our current era dominated by AI and algorithms.

² Susanne Langer’s term “significant form” refers to the way art and symbolic forms embody and communicate meaning. It is the aspect of a work that gives it expressive power, resonating deeply with the observer, providing insight into our human condition. These forms serve as a medium for expressing the ineffable aspects of human experience, bridging the gap between subjective inner life and objective reality; for Langer this is another way to make rational objective statements of the world.