2016: The Year Music Changed and the Machines Didn’t Notice

Why Your Music No longer Holds Time (And the Cost to Our Shared Understanding)

Church bells ringing in the distance. I never gave much thought to them. As an American, I rarely heard them except when the local church in my small town rang them during parades or holidays. If they carried deeper meaning, it went in one ear and out the other.

In Europe, however, church bells have long structured daily life. Since the early medieval period, their ringing has marked the hours, announced births and deaths, warned of danger, and called communities to worship. The bells acted as sonorous embrace, enveloping a community, creating a morphology that made legible the mundane with the sacred, the private with the public, and making time itself felt.

By the 1860s, this sonic commons began to lose its coherence. The French historian Alain Corbin, in Village Bells: The Culture of the Senses in the Nineteenth-Century French Countryside, traces how the very bells that once provided a field of knowledge, now provoked widespread complaint as noise. ‘From this date on,’ he observes, ‘there was a greater determination to lay claim to one’s morning sleep.’¹

In this essay, I trace how the transformation of church bells from communal resonance to private noise prefigured our current algorithmic sonic order — and how Pandora’s new dataset unexpectedly reveals this centuries-long arc now determines what flows through your earbuds.

When Pop Music Went Narrow and Minor

Music datasets used to train both algorithmic and generative AI systems are everywhere right now. I wrote an absurdly long piece² about Meta’s attempt to quantify ‘beauty’ using some of these datasets. While working on that article, I downloaded and reviewed some of the training data Meta used — and let’s just say, a lot of it is garbage.

I spent 17 years working as a music analyst on the Music Genome Project. When I joined, the company was called Savage Beast Technologies. It later rebranded as Pandora Media and launched Pandora Radio in 2005 — back when streaming’s dominance was far from inevitable.

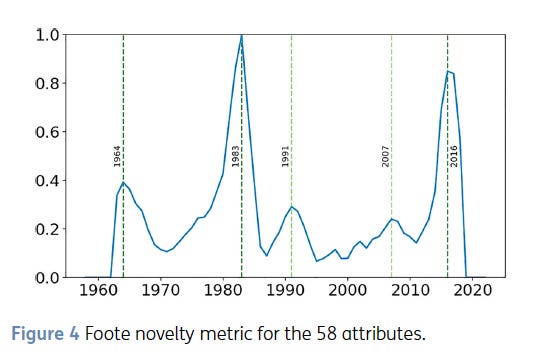

Pandora recently released MGPHot³, a dataset of 21,000+ Billboard Hot 100 songs spanning 1958 to 2022. Unlike most music datasets that rely on automated feature extraction, MGPHot represents something unprecedented: trained music analysts spent an average of 15 minutes carefully listening to each song. This human analysis revealed what no algorithm had detected — popular music underwent a seismic shift in 2016.

To surface these seismic shifts in music, the researchers applied a pattern-detection algorithm⁴ to this human-curated data and it revealed these changes: 1964 (rhythm), 1983 (instrumentation), and 2016 (something entirely different).

Lat’s review the two previous big peaks.

Beatlemania

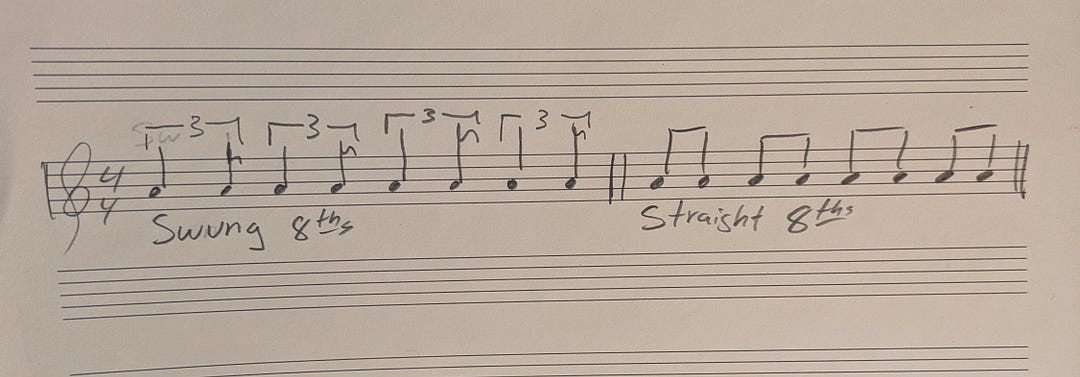

The MGPHot analysis revealed that 1964’s revolution centered on rhythm — a structural shift that reshaped rock and roll’s underlying feel. Before 1964, much of popular music was written in compound meter — 6/8 or 12/8 — where eighth notes are felt as part of a triplet grouping. This gives the music a ‘swinging’ or lilting quality, where the beat is subdivided unevenly: long-short, long-short. Kind of like how you walk after a few drinks.

In 1964 the dominant feel shifted toward straight eighth notes in 4/4 time. You can hear it clearly in The Beatles’ ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand,’ a song that exemplifies this newer, driving rhythm that would become the default rhythm of rock and pop for the next fifty years.

The Rise of Synthesizers

1983 represents the year I bought my first cassette tape — Michael Jackson’s Thriller — and it also represents the next major shift in pop music. This time it was not the rhythm that changed but the type of instruments being used and the way this changed the overall timbre of the music.

The shift was from guitars to synthesizers.

In fact Michael Jackson’s album Thriller is a great example as it incorporates heavy use of synthesizers.

The Minor Revolutions 1991 & 2007

1991 saw the arrival of “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” yet this resulted in only a minor bump in the data. The main thing here is that most music in the Billboard Hot 100 was still not grunge music. I remember living this era — there was this pull of two different worlds happening at once: Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Stone Temple Pilots, Primus on one end and TLC, Janet Jackson, Paula Abdul, Boyz II Men on the other.

Similarly, 2007 registered as another minor peak, characterized by what researchers identified as “the rise of happy lyrics” and a brief reversal in the longer trend away from major harmonies — think Beyoncé’s “Irreplaceable” topping the charts that year.

2016 Story

The 2016 peak tells a different story. Unlike the single-factor revolutions of 1964 and 1983, where rhythmic feel or instrumental timbre shifted, the 2016 rupture saw multiple dimensions of musical meaning converge simultaneously.

The MGPHot researchers identify changes in harmony, vocals, lyrics, and compositional focus — specifically, a move away from riffs and elaborated song forms, and a distinct loss of melodic focus. Crucially for my later argument, vocal timbre itself transformed: voices in the Hot 100 became more nasal and less dynamically expressive. This was accompanied by what the researchers call ‘a tremendous increase’ in explicit language and a move toward synthetic sonorities.

These shifts correspond to hip-hop’s ascendance as the dominant force in modern popular music. What was once an underground, counter-cultural critique of mainstream pop has been absorbed by mainstream.

I believe the specific data points surfaced in the 2016 shift speak to a much deeper cultural, technological and ontological shift, that I am going to explore in the next few sections and return to a further analysis of this at the end of the piece.

“This is my natural rhythm. It’s how I bob my head.” — J Dilla

Last year, I published a piece on what I call the griddification of music ⁵— a concept I’ve since pitched to several PhD programs for formal research. My argument: by subjecting musical expression onto digital grids, we’ve severed music’s ancient function as the carrier of embodied temporal knowledge between human beings.

What the Pandora MGPHot dataset now reveals is that we’re experiencing an inverted Tower of Babel. Where the original Tower scattered unified language into incomprehension, we’re compressing diverse musical expressions into a singular, flattened grid. The cost of this supposed ‘clarity’ and ‘efficiency’? The erasure of meaning itself. Quantized and sliced into patterns no human would naturally perform, this music strips us of our ability to express and understand each other’s lived time — something humans did for millennia until the last 25 years.

The Objectification of Time

Susanne Langer’s philosophy of art⁶’⁷ provides the theoretical foundation for understanding why griddification represents such a profound cultural shift.

For Langer, music is the objectification of felt time⁷ — the transformation of our inner temporal tensions, the concurrent flux of emotions and organic rhythms, into audible forms that carry vital knowledge we can only access through experiencing them musically. These audible forms make the structure of lived experience perceptible, allowing us insight into our reality that language cannot provide due to its ontological limitations.

But Langer warns that this profound capacity remains meaningless without what she calls musical hearing — a cultivated form of intentional listening. Already in 1953’s Feeling and Form⁷, she identified radio’s convenience as dangerous, allowing unintentional listening while doing other activities. She called this what we now know as lean-back listening ‘the very contradiction of listening.’

If radio began this shift, the Walkman completed it. After 1979, we could finally shut out the world entirely⁸:

By the mid-1990s, the privatization of listening met its perfect counterpart: the griddification of music production. When DAWs quantize musical expression onto the grid, they erase what Langer identifies as music’s fundamental power to symbolize ‘forms of sentience.’ The dynamic flux that constitutes the semblance of experiential time collapses into clock time — the one-dimensional continuum that abstracts away the concurrent, tension-layered, and embodied aspects of temporal life. This is the time of modern instrumentalized life — and the root of our collective anxious, unmoored gestures.

We do not experience life as clock time. Yet our music, the primary means through which humans have always shared their inner temporal experience, has been rendered mute by griddification. No longer able to carry genuine lived time, music cannot make our actual experience perceptible to others. The consequence is tragic: we are losing the ability to understand each other.

***What about dance music, which is intentionally made to the grid? When performed through a DJ, either solo or in a club setting, this music can still express lived time. More on that in a future essay. ***

The argument I’m making is no small quibble. The felt dynamics of inner life — the ethical, epistemological, and ontological responses embedded within those temporal fluxes — have been excised, silenced, and rendered to a nullity. We are left unheard and unseen within one of the most vital symbolic domains through which human understanding once flowed. In its place now flows perfectly exchangeable, universalized content. That ever-present anxiety you feel? It is capital flowing not with your beautiful haecceitas, but through circuits of modular quidditas — flattened resemblances designed for circulation, not relation. You are no longer heard, because your time — your actual, felt temporality — does not register in systems built to recognize only the quantifiable.

Your raw, numb fingertip swipes just one more time looking for recognition, to only be met with another perfectly unembodied machinic gesture.

Recent Neurobiology Confirms Langer’s Philosophical Insights

Contemporary neuroscience has begun to validate Langer’s foundational claims — though I’ve yet to see any study acknowledge her prescient work from 70 years ago. Recent findings reveal precisely how the brain processes musical time, and what gets destroyed when digital tools flatten expression onto the grid.

Bonetti and Brattico’s study, Brain recognition of previously learned versus novel temporal sequences⁹, provides particularly compelling evidence. When listeners recognize previously learned musical sequences, their brains exhibit simultaneous processing at multiple temporal scales: faster oscillations (2–8 Hz) track local sensory details, while slower oscillations (0.1–1 Hz) integrate these into a coherent temporal whole.

This dual processing reveals that musical meaning emerges from the brain’s capacity to integrate temporal information across hierarchical levels — precisely what griddification destroys when it reduces musical expression to discrete, quantized events.

Brattico, presenting this research, makes the destruction explicit:

Sounds that are isolated might not mean anything really. When they are integrated and they become a melody, they acquire novel meanings that would not be carried by the single sounds alone.¹⁰

This integration occurs through memory-based prediction operating across what she identifies as five hierarchical levels:

from simple transitions to chunking, to ordinal knowledge, to abstract regularities, to rule processing.¹⁰

When DAWs quantize musical performances onto the grid, they sever these integrative processes, rendering music unable to carry the temporal knowledge that emerges from embodied human performance. This creates a deformed gestalt: listeners can no longer perceive a legible temporal whole because the griddified music embodies machinic rather than human expressions of time, disrupting the brain’s capacity to recognize and integrate lived temporal experience.

Brattico also critiques the research in her field which often relies on ‘repeated isolated sounds’ performed using MIDI and unnatural instrumentation, arguing that this approach fails to capture the organic complexity of musical expression. As she notes:

Phenomenologically, making sense of real music does not correspond to listening to repeated isolated sounds. It has to be much more complex and has to cover all five levels.¹⁰

This methodological reduction treats music as assemblages of discrete units rather than the flowing temporal gestalts through which embodied knowledge becomes audible, severely limiting our understanding of how music actually functions as a carrier of meaning.

The audio is fixed ~5:12 mark — RITMO Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Rhythm, Time and Motion

Why Platforms Fear Musical Complexity

The implications of Brattico’s findings extend far beyond the laboratory. This neurobiological understanding of how musical meaning emerges through temporal integration reveals why platform algorithms systematically avoid such complexity.

Platforms like Spotify deliberately curate playlists designed to maintain users in a steady, non-activating state¹¹ — the lean-back experience — rather than serving music that would trigger strong responses and pull listeners into active integrative engagement¹¹.

Music that might provoke what Langer described as the full unfettered ‘objectification of felt time’ — the kind of temporal complexity that demands integrative processing — is systematically filtered out in favor of content that keeps users on-platform, producing data to harvest and sell and of course receptive to advertising.

Music with its edges rounded off creates a sonic environment optimized for data extraction and sustained engagement metrics¹¹. Recent neuroscientific research on both compromised reward systems and reduced aesthetic processing supports this analysis, demonstrating that when temporal complexity is diminished, the brain shifts from integrative aesthetic engagement to passive sensory processing¹²’¹³’¹⁴— all the more receptive to the circuits of capital circulation.

This flattened interchangeable musical landscape however does serve a broader logic, as the primary training data for generative AI systems which thrive on predictability.

What Is Latent Space In AI And Why It Is Important

When a generative AI model ‘learns’ from the data it is trained on, it creates a high-dimensional mathematical space that is a compressed map of the patterns and relations the model has developed during its training process. This internal virtual structure is called a latent space.

This latent space is not where the data is stored, such as all the copyrighted songs a model like Suno.ai has been trained on¹⁵, but rather the associations the model made such as ‘minor key,’ ‘fast tempo,’ ‘distorted guitars,’ ‘Americana style,’ ‘rap music,’ etc.

When you prompt an AI model to generate a song, the model navigates this latent space to assemble a new output. It pulls from the learned patterns and associations within the space to produce something that resembles the kinds of music it was trained on, filtered through your prompt.

But it is the initial state of the generation process that most interests me. Models like Suno.ai begin by sampling pure noise, random data with no inherent musical structure. The latent space is used to progressively shape this noise, step by step, into something recognizable. When you type ‘make me a folk song about my dog and cat having a falling out over the cat sleeping in the dog bed,’ the model does not start with a piece of music, but with noise.

It is from this point that the model then refines the noise into audio signatures associated with folk music, instrumentation, and tempo etc. The exact process that that Suno.ai uses is unknown but we can reasonably speculate it uses a guidance model to compare each step to the intended meaning of the prompt, refining the noise into structured musical output.

So we have:

Noise → progressively denoised and guided → guidance model checks for alignment (folk song about cats and dogs) → model refines output toward alignment → repeat many times → user receives song that can plausible be argued sounds like a folk song about cats and dogs.

This process has significant ramifications for what is considered a valid output and what is considered ‘noise.’ In a system that only recognizes what it has already encoded, are church bells carriers of information, or noise?

To Be Seen or Not to Be

I just want to be seen (and understood).

This, arguably, is the most fundamental aspect of modern life: to be seen, to be heard, to be understood through the mediating structures that now organize social visibility.

When we tap out a Tweet, share a selfie, make a tik tok video or anything we do, all of these gestures are rooted in our desire to be seen, heard, and hopefully understood.

The media and technology researcher Eryk Salvaggio outlined this process in a recent talk given at the Artificial Intelligence & Contemporary Creation conference in Paris¹⁶, titled Human Noise, AI Filters: ‘Mr. Watson, Come Here.’¹⁷

Salvaggio’s analysis reveals how latent space functions as a gatekeeper of existence itself. Within a generative AI model, to be seen, heard, or understood requires that what you are has already been said, heard, and understood within its training data. If you fall outside what the latent space encodes, you are not heard, seen, or understood — you do not exist within the model’s constructed world.

In this latent space, I see a centuries-long project reaching its culmination. Before Copernicus, humans inhabited a cosmos where everything had its place, where meaning was given, where existential anxiety was impossible because the order was complete. The Copernican rupture shattered this certainty, leaving us adrift. Ever since, modernity has desperately sought to restore that lost totality of meaning. Now, generative AI offers a perverse solution: a new closed cosmos where everything that can be known is already encoded, where all possible futures are predetermined, where existential anxiety is replaced by algorithmic certainty.

We no longer face an infinite horizon of possibility, but a predefined set of futures, each one already mapped within the latent space. The Eternal Return has been operationalized: not as Nietzsche’s demand to affirm life in all its chaotic fullness, but as algorithmic recursion — an endless loop of past data reshaped into plausible simulations of novelty. God is no longer dead. He has been resurrected as a predictive model, determining which futures are permitted to appear.

The Recursion Feedback Loop Of An Operationalized Machinic Culture

A line I am trying to draw around this enclosure of human expression, could be interpreted as smuggling in a normative claim that the music being produced today is bad and that what I am laying out here is really just a fancy version of the Get Off My Lawn meme.

But the 2016 shift the MGPHot dataset identified reinforces everything I’ve traced here: the complete capture of our sonic commons by machinic logic. Hip-hop’s transformation is perhaps the starkest example — a genre that once shattered linear time through sampling, combined with complex rhythmic poetry, now produces the smooth, efficient, predictable temporalities platform capitalism requires. What was counter-cultural resistance has become the primary vehicle for capital’s sonic agenda.

The transformation is perhaps most starkly visible in how rap itself is now created. The “punch-in” method — where artists mumble fragmentary lines one at a time directly into Pro Tools, building songs from discrete units rather than continuous flow — represents the complete detemporalization of musical expression. As documented in the New York Times’ examination of this practice¹⁸, modern rappers no longer write verses that unfold through time; they accumulate atomized moments, each line existing as an isolated data point to be arranged and rearranged within the DAW’s grid.

Video: Why Rappers Stopped Writing: The Punch-In Method

The rough edges that made hip-hop meaningful — its temporal disruptions, its political urgency, its Dilla-time feel — have all been smoothed for frictionless circulation. Stripped of its singular haecceitas, the music becomes an empty vessel. Its interchangeable beats and patterns form an amorphous pastiche onto which listeners project their anxieties as they prance before billions of smartphone cameras, screaming — see me, see me, please just acknowledge me. These very anxieties will themselves be captured and fed back into the global capital carousel producing more data and more wealth for the architects of this platform economy.

The MGPHot dataset pinpointed the exact moment when the platform economy gained full control of our musical cultural sphere. Nasal, narrow voices optimized for non-invasive earbud listening, minor keys that facilitate lean-back dissociation, the complete absence of any key changes in popular music¹⁹ and completely synthetic virtual instruments embedded within griddified DAW architecture — all enabling what the industry celebrates as ‘efficient,’ ‘tight,’ ‘clean,’ predictable production.

Need to make it feel a little human? Set the quantize function with a 2% error rate. Voilà — human ‘imperfection,’ simulated just enough to be legible. NEXT!

This profound ontological rupture in how time itself is experienced through music is going completely unrecognized by our cultural, scientific, political, and spiritual communities. Meanwhile, the loss of music’s epistemological, ethical, and singular haecceitas — its power to carry embodied knowledge — is tearing apart our communities, our cities, our nations, and our very ability to recognize each other in our full humanity.

Something has gone terribly wrong. And what are we offered? Only the ever-diminishing dopamine hit of another swipe, another directionless anxious gesture we send into the void, over and over and over again — hoping, or is it despairing, to be understood — as we passively consume music of monstrous perfection while producing more data for the insatiable machinic order.

We may be suturing the Copernican rupture, but at an incredible price: church bells have become noise, and inhuman expressions of time have become our training ground for a future of absolute predictability.

CITATIONS

¹ Corbin, A. (1998). Village bells: The culture of the senses in the nineteenth-century French countryside (M. Thom, Trans.). Columbia University Press. https://cup.columbia.edu/book/village-bells/9780231104500

² Anthony, J. (2025, February 17). Can AI measure beauty? A deep dive into Meta’s audio aesthetics model: A critical examination of Meta’s AI aesthetic evaluation model. Medium. https://medium.com/@WeWillNotBeFlattened/can-ai-measure-beauty-a-deep-dive-into-metas-audio-aesthetics-model-e988397c12db

³ Oramas, S., Gouyon, F., Hogan, S., Landau, C., & Ehmann, A. (2025). MGPHot: A dataset of musicological annotations for popular music (1958–2022). Transactions of the International Society for Music Information Retrieval, 8(1), 108–120. https://doi.org/10.5334/tismir.236

⁴ Foote, J. (2000). Automatic audio segmentation using a measure of audio novelty. In IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (Vol. 1, pp. 452–455).

⁵ Anthony, J. (2024, September 17). Red vs. Blue: Is modern music production driving our political divide? How the early 2000s adoption of DAWs and AI tools coincides with America’s growing political divide. Medium. https://medium.com/counterarts/red-vs-blue-is-modern-music-production-driving-our-political-divide-50fec9b1da60

⁶ Langer, S. K. (1957). Philosophy in a new key: A study in the symbolism of reason, rite, and art (3rd ed.). Harvard University Press.

⁷ Langer, S. K. (1953). Feeling and form: A theory of art. Scribner.

⁸ Anthony, J. (2025, May 21). How the Walkman taught us to be alone: Tracing the collapse of shared reality from the HOT LINE button to Spotify’s algorithmic control. Medium. https://medium.com/thought-thinkers/how-the-walkman-taught-us-to-be-alone-d88b220293b7

⁹ Bonetti, et al. (2023). Brain recognition of previously learned versus novel temporal sequences: A differential simultaneous processing. Cerebral Cortex, 33(24), 5524–5537. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhac439

¹⁰ Brattico, E. (2023, May 9). RITMO Seminar Series: Making sense of complex music — Insights from neuroimaging [Video]. YouTube.

¹¹ Pelly, L. (2025). Mood machine: The rise of Spotify and the costs of the perfect playlist. Atria/One Signal Publishers.

¹² Dai, R., Toiviainen, P., Vuust, P., Jacobsen, T., & Brattico, E. (2024). Beauty is in the brain networks of the beholder: An exploratory functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000681

¹³ Brattico, E., Brusa, A., Dietz, M., Jacobsen, T., Fernandes, H. M., Gaggero, G., Toiviainen, P., Vuust, P., & Proverbio, A. M. (2025). Beauty and the brain — Investigating the neural and musical attributes of beauty during naturalistic music listening. Neuroscience, 567, 308–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2024.12.008

¹⁴ Stupacher et al., (2025). Individuals with substance use disorders experience an increased urge to move to complex music. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(20), e2502656122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2502656122

¹⁵ Mauran, C. (2024, August 2). AI music startup Suno admits to using copyrighted music, but says it’s “fair use.” Mashable. https://mashable.com/article/ai-music-startup-suno-admits-using-copyrighted-music-says-its-fair-use

¹⁶ Presented at the L’IA en question, questions à l’IA event, 24–25 May 2025, Centre Pompidou, Paris. https://www.centrepompidou.fr/fr/programme/agenda/evenement/BeSclg1

¹⁷ Salvaggio, E. (2025, May 25). Human noise, AI filters: “Mr. Watson, come here.” Talk given at Artificial Intelligence & Contemporary Creation conference, Centre Pompidou, Paris. https://mail.cyberneticforests.com/human-noise-ai-filters-mr-watson-come-here/

¹⁸ Coscarelli, J., & Throop, N. (2023, September 20). ‘No pen, no pad’: The unlikely way rap is written today. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/20/arts/music/punching-in-rap-video.html

¹⁹ Seshadri, M. (2022, November 30). Where did all the key changes go? Music Features. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2022/11/30/1139707179/where-did-all-the-key-changes-go